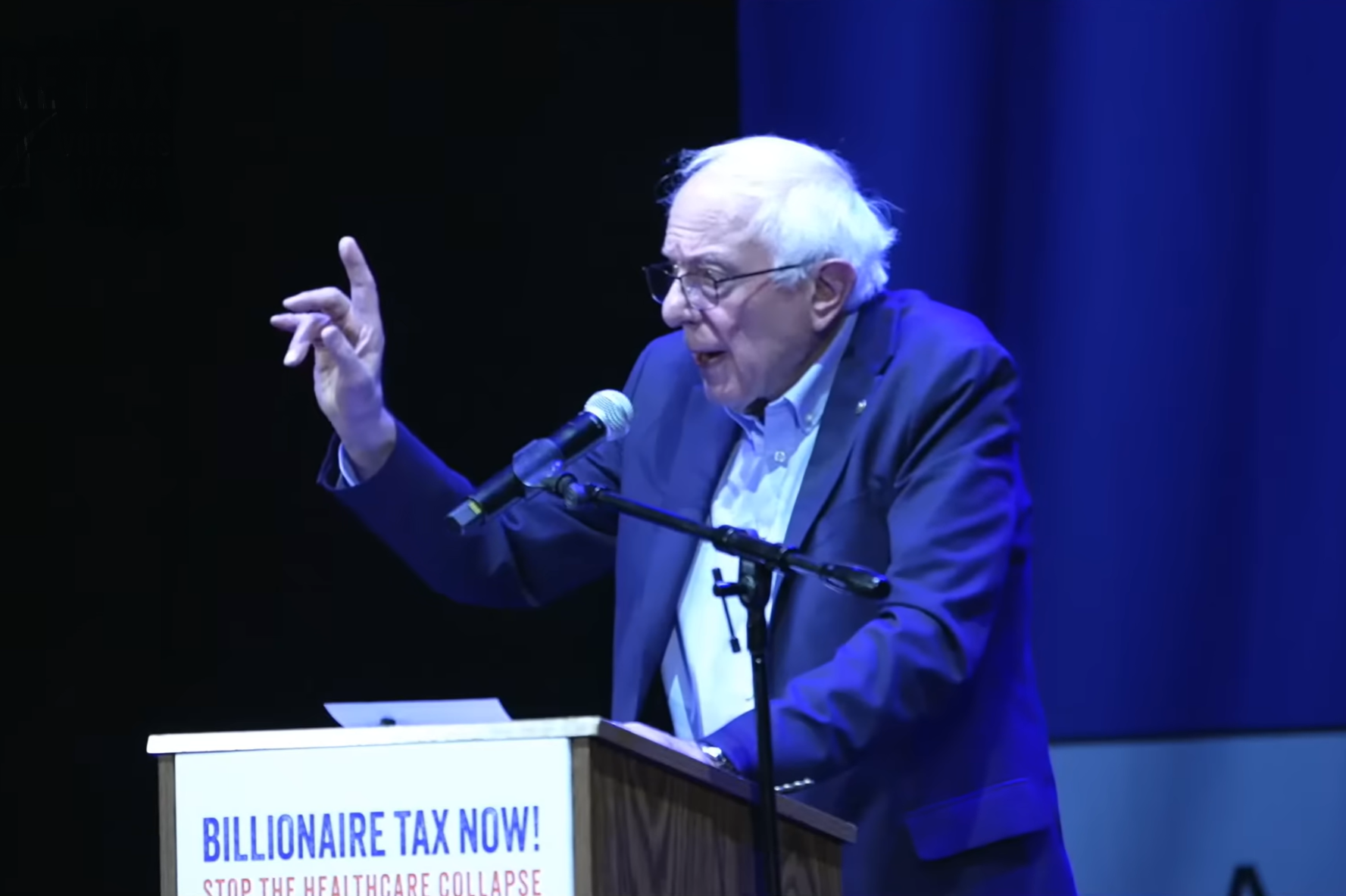

Feb. 23 — Before jurors left the courtroom to deliberate, the prosecutor took a final shot at the six former City Council members accused of corruption.

“The one-percenters of Bell,” he called them, a band of small-town politicians who had “apparently forgotten who they are and where they live.”

After four weeks of testimony, a jury of seven women and five men was handed the fates of six onetime civic leaders accused of raiding the small town’s treasury with huge salaries.

Jurors now must decide whether it was legal for Luis Artiga, Victor Bello, George Cole, Oscar Hernandez, Teresa Jacobo and George Mirabal to receive salaries as high as $100,000 a year, spiked by pay for serving on city boards that the prosecution insisted seldom met and did little work.

If convicted, the former officials — one a preacher in town, another a retired steelworker — could be sentenced to prison.

The huge salaries in Bell were exposed in 2010, an era when the town’s finances were sagging, workers were being cut from the city payroll and a long-promised sports park remained fenced off.

While the prosecution cast the six as thieves who thought more of their own wallets than their constituents’ needs, defense attorneys argued their clients were tireless advocates in a town that had been forced to weather the misdeeds of a scheming, ruthless city manager.

They stressed to jurors that the prosecution failed to prove criminal negligence — that their clients knew what they were doing was wrong or that a reasonable person should have known.

Throughout the trial, the defense maintained that their clients relied on experts to tell them if their salaries were illegal. Stanley L. Friedman pointed out that his client, Hernandez, had only an elementary school education and was elected for his heart, not his intellect.

“There’s a lot of elected officials who we have quite a bit of respect for who maybe, maybe, weren’t the most scholarly,” Hernandez said, mentioning former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Cole, Jacobo and Mirabal, the only defendants to take the stand, said independent auditors and former City Atty. Edward Lee never raised concerns about their paychecks. Although Lee was on the prosecution’s witness list, neither side called him to the stand.

The defense pinned much of the blame on a culture where City Administrator Robert Rizzo ruled with a strong hand, drafting resolutions for salary increases and manipulating council members to take city money. Cole testified that he voted in 2008 for a 12% annual pay raise because he feared Rizzo would gut the community programs he helped develop.

“We’re here for Mr. Rizzo’s sins,” said defense attorney George Mgdesyan.

His client, Artiga, a pastor at Bell Community Church, said people around the country were praying for him. “I believe God already has set in motion that I will be found not guilty,” said Artiga, who days before his arrest described his bountiful salary as “a trap from the devil.”

At the center of much of the trial was Bell’s charter, which was passed in a 2005 special election in which fewer than 400 people voted. The charter allowed Bell greater flexibility in governing itself than if it had remained a general law city.

However, Miller argued that the charter limited council members’ annual pay to what state law dictated a city of a similar size could receive. That amount — $8,076 — was paid to Lorenzo Velez, the lone sitting council member in 2010 who was not charged with a crime. Velez said he was unaware how much his colleagues were making until the salaries were revealed by The Times.

Velez’s salary, as well as the council’s refusal to answer a resident who asked during a 2008 meeting how much they were being paid, was proof that defendants knew their pay was illegal, Miller said.

“They knew they were in trouble,” he said.

The defense insisted that the charter allowed their clients to be paid extra for city boards, such as the Surplus Property Authority, and that those raises were voted on in open session.

Defense attorneys also urged jurors to take into consideration the character of their clients, who multiple witnesses had testified were so dedicated to their community that they often put residents ahead of their own family.

Miller cautioned that a person who is well-liked can still commit a crime.

“A liquor store robber’s weapon is a gun,” he said. “The weapon of the white-collar criminal is the trust he or she has gained over a number of years that allows them to occupy positions of elevated trust where they can steal a large amount of money.”

——————–

Copyright 2013 – Los Angeles Times

Thanks for reading CPA Practice Advisor!

Subscribe Already registered? Log In

Need more information? Read the FAQs

Tags: Income Taxes