Your identity has already been stolen, whether you know it or not, according to one of the most senior identity theft experts in the world.

Fraud is costing Americans almost a trillion dollars a year – as of the end of 2015, the annual cost had hit $994 billion. And identity theft continues to be one of the fastest growing in the U.S., as most Americans are voluntarily giving away most of their own data via not only social media like Facebook, but also through overly casual government use of important information. Even more worrisome: Children are the most lucrative targets of identity thieves.

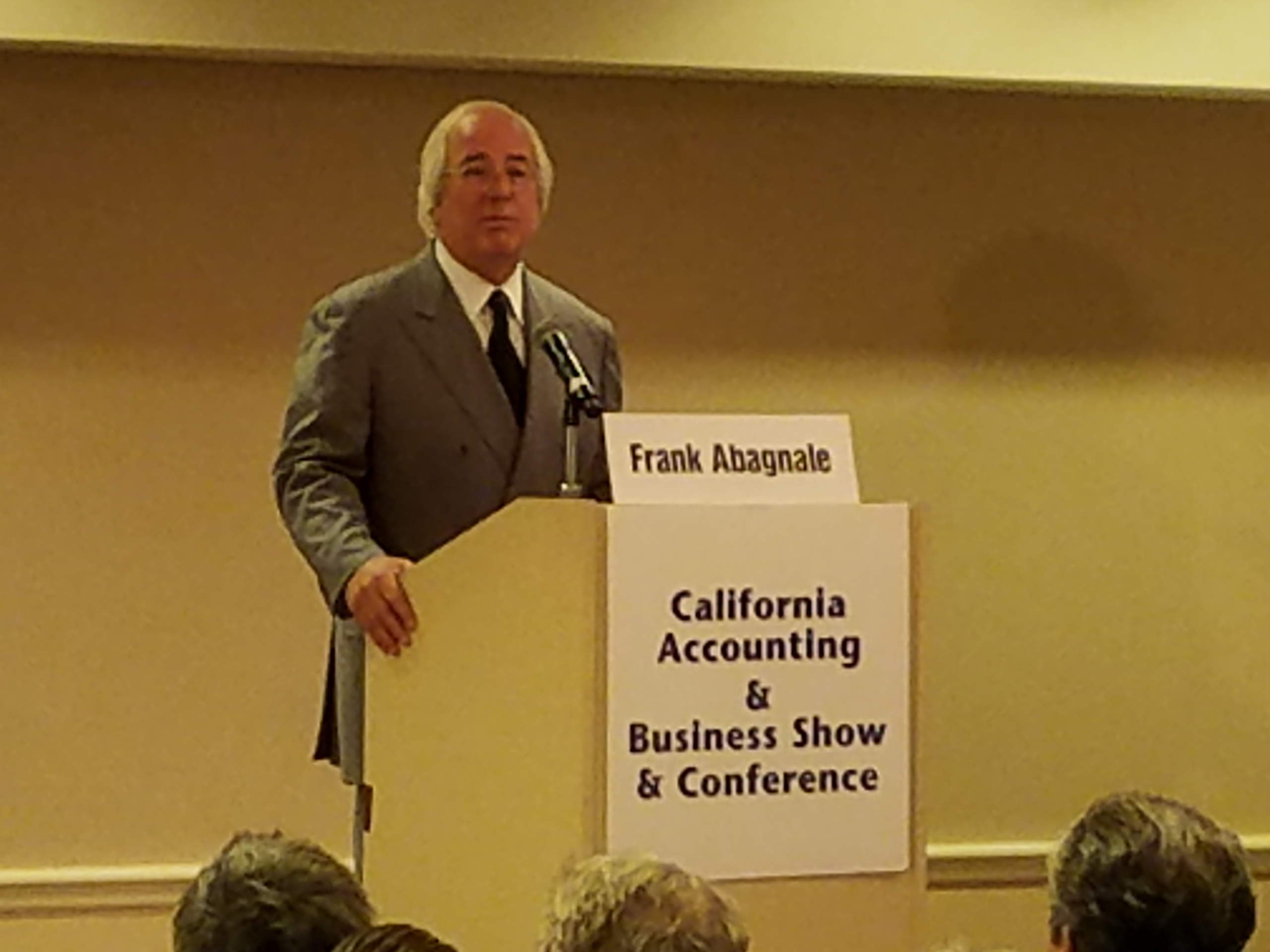

Those were among the core focus areas of a keynote speech by Frank Abagnale, as the 2016 California Accounting and Business Show and Conference got underway on Wednesday at the LAX Hilton in Los Angeles. This is the 32nd year of the conference.

“We share everything. We tell people everything about ourselves and then wonder how the identity thieves got ahold our information,” he said to a gathering of more than 300 CPAs and financial professionals. “People need to remember that their private information is the last thing they have left of their identity.”

In short, he says, we’ve all had our private information exposed and collected by criminals who may someday sell the information or use it themselves. If they haven’t done so yet, it is because it may be being warehoused, but while credit cards and bank numbers can be changed, most people will never change their Social Security numbers or names.

Abagnale was the real-life inspiration for the character played my Leonardo DiCaprio in the 2002 movie “Catch Me If You Can.” The film, based on his life, was about a young con artist who forged checks and impersonated an airline pilot, doctor and lawyer during the late 1960s. Abagnale was ultimately caught and convicted of fraud by French authorities, and served six months of a one-year sentence at the French Perpignan prison. Steven Spielberg, who directed the film adaptation, visited the prison and noted that there was no mattress, blanket or electricity, and only a hole in the floor for a toilet.

Abagnale subsequently was then sent to Sweden to face similar charges and served a six-month sentence in a Malmö. After extradition to the U.S., he was again convicted and sentenced to 16 years, but his sentence was reduced and an arrangement was reached through which he would be released early on the condition that he work with the FBI, helping on fraud and forgery cases.

He is now the CEO of Abagnale and Associates, which provides security and document consulting services. More than 14,000 financial institutions and companies have adopted fraud prevention programs that he has developed. Abagnale has also been credited with many U.S. agencies removing Social Security numbers from identification cards, mailing envelopes, postcards and other documents.

Abagnale says social media, particularly Facebook and LinkedIn, are exceptionally concerning because people offer birthdates, photos, and often much more important information to whoever has access to their pages. These things might not just be used by thieves, but also by future employers.

“What you say on social media can stay with you, even if you think you’ve deleted it,” Abagnale said. “A 13 year-old who finds a fascination with bombs, or who uses an inappropriate term may find that those comments can still be attributed to them 10 or more years later.” This may not be fair, he noted, but it is simply how we have chosen to start exposing our personal information and reducing our own privacy.

Abagnale said that, comtrary to the movie’s portrayal, he never saw his father again after 10th grade, when his parents had filed for divorce and a judge had asked him to select which parent he wanted to live with. He says he had been traumatized by the choice, and instead of choosing one over the other, he ran.

His con artist days started, he said, in high school. His friends had noted that he looked more like a teacher than a student, particularly on days when his Catholic school required students wear a suit. He then altered one digit on his drivers license birthday, adding a decade to his age. With a legitimate checking account, he also started to overdraw his account at various New York banks. He soon saw the airline flight crew, and pilots, as depicted in the movie, forged a pilot ID and obtained a uniform, all through casual deceptive practices.

Although he impersonated a PanAm co-pilot, he never flew on PanAm flights, according to both Abagnale and PanAm. He said this was because he wasn’t sure his bogus ID and backstory would pass the scrutiny of an actual PanAm crew. Instead, he used airline hospitality, which allowed flight crews from other airlines to fly free when space, or pilot jumpseats, were available. Airlines also honored personal checks from pilots of all airlines, and had hotel accommodations in various cities, which Abagnale took advantage of through forgery.

Over the five years he was committing the cons, Abagnale reportedly flew more than one million miles on 160 flights, visiting 26 countries. Although it is stated that Abagnale impersonated an attorney, he did actually pass the Louisiana state bar exam legitimately. He was never caught or fired for his impersonations of a lawyer or doctor.

Since then, he has written several books, including the 1988 book, Identity Theft, in which he foretold many of the coming issues of the phenomenon, and the 1996 book, The Art of the Steal. He has also helped design security features that are used in checks used by most Fortune 500 companies and payroll providers. Intuit, which makes small business management software, also uses his security features and sponsors his briefings around the nation.

Even with good technology, he says, breaches are often a matter of human error. Whether it’s the state of South Carolina’s recent breach of information on every single taxpayer in the state, or similar instances at the Office of Personnel Management or Target. There are also serious flaws in security processes that need to be addressed.

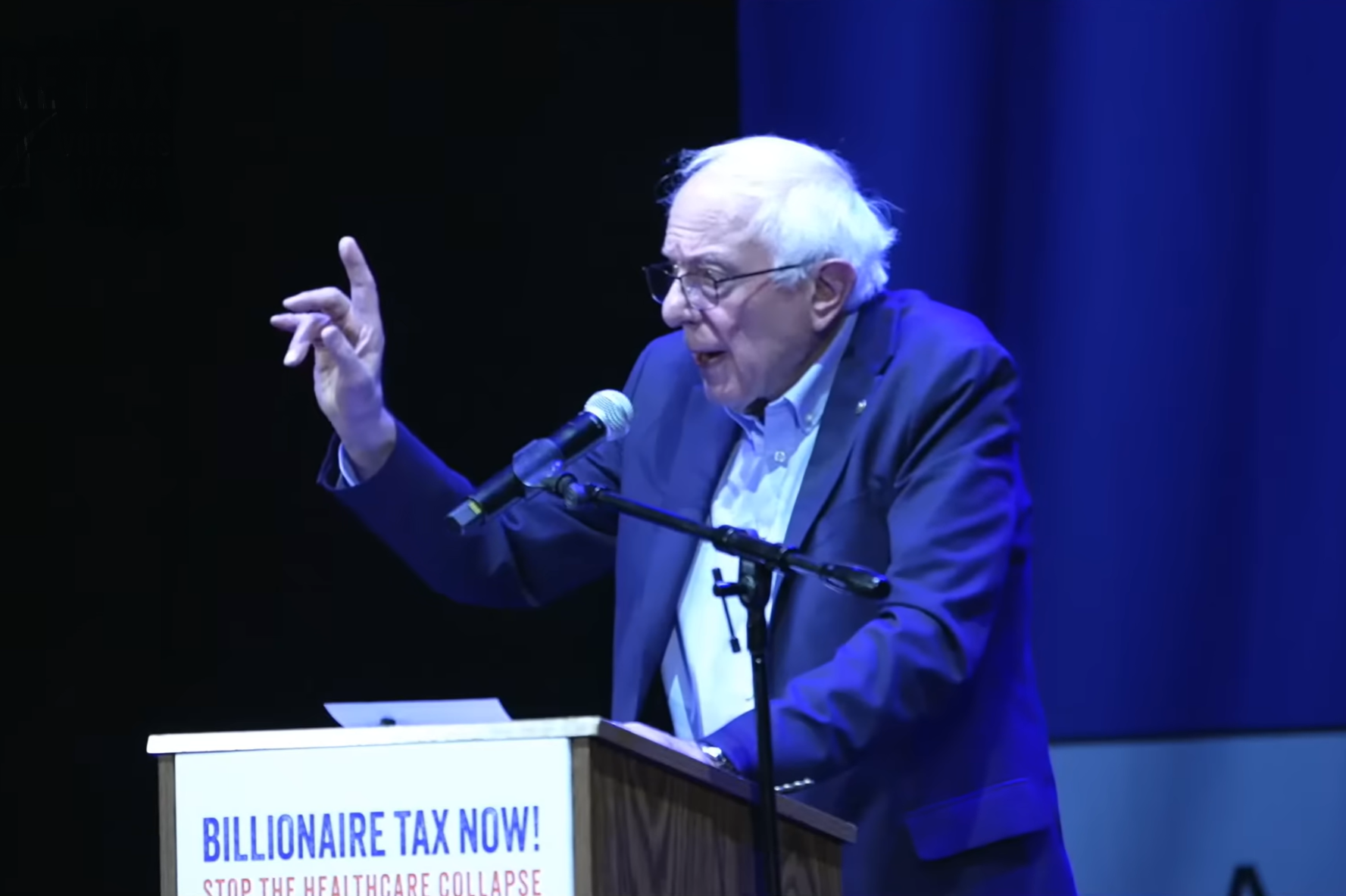

For instance: “How can the IRS not notice that it sent 1,700 income tax refunds to the same address in Lithuania?” he asks incredulously. This is a perfect example of why “the government is the easiest target for hackers and scammers: because it has the most money.” And while he notes that most of the major breaches and cons are being perpetrated by criminals in Eastern Europe, Russia and China, some of the money is ending up back in the U.S. in the form of drugs, porn and child sex trafficking.

Some of the major frauds in the U.S. each year, he said, include Medicare and Medicaid fraud ($100 billion), unemployment fraud ($7.7 billion), EITC fraud ($16 billion), tax refund fraud ($5.6 billion), food stamp fraud ($3 billion). New threats we need to figure out how to address include the selling of newborn Social Security numbers by hospital staff, and digital images that are stored on photo copiers- that can be retrieved when the machines are later sold as used or for scrap. It’s an identity thief’s goldmine, he said.

Abagnale has now spent more than 40 years with the FBI, and has been married to his wife for 39 years. They are the parents of four children, one of whom is an FBI special agent. He says that his role as a parent, as a father, is the most important he will ever have.

“God gave me a wife, and these four wonderful children, and she changed my life. Everything I am today I am because of her,” he said. “And every parent knows, no matter your age or your children’s age, the last thing you think and worry about every night is your children. And to the men in this room, being a man has nothing to do with money, it is about knowing how to love and be faithful.”

Although he’s been made famous by the movie, a novel, a broadway musical and the television show “White Collar,” all based on the his life story, he said he wants to stress that what he did was wrong.

“Every day I live with the burden that what I did was illegal, immoral and unethical,” he said.

Although he never saw his father again after age 16, he noted his respect for him, while also ruing the loss of his own childhood.

“I had a daddy who loved his kids. He always told us he loved us and never missed a night. As much as we treat 16 year-olds as adults, they are still kids, and all kids need their mother and their father. Divorce is devastating for a child to deal with. The judge, a stranger, told me to choose between them … so I ran. And I cried myself to sleep until I was nineteen.”

Thanks for reading CPA Practice Advisor!

Subscribe Already registered? Log In

Need more information? Read the FAQs

Tags: Taxes